Table of Contents

The Discussion section of scientific paper is a tricky piece of writing that can challenge even the most seasoned academic. In this post, we take a look beyond the basic structure and take a deep-dive into the backbone of any good Discussion: the argument. How to construct one, and what makes a good argument so interesting?

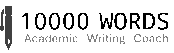

The structure of the Discussion section

Generally, the Discussion is structured into an introduction, middle, and ending. If there is an introduction, it often restates the research questions, key results, and sometimes a key conclusion. The next paragraphs form the body of the discussion, where the actual discussing of the results takes place. Finally, there is usually some paragraph that wraps things up.

The middle paragraphs is what this blog post is all about. These paragraphs are, in my experience, by far the toughest to write.

What is an argument?

In essence, each paragraph of the Discussion section forms an argument about one or multiple results. This is usually some elaborate form of “We found x, therefore y is true.”

According to Wikipedia “an argument is a series of statements, some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion”. To give a few examples:

Premise: The sun rises every day.

Conclusion: The sun will rise tomorrow.

Premise: All apples are green.

Premise: This is an apple.

Conclusion: This apple is green.

Or a bit more scientific:

Premise: Climate is the principal factor defining the potential distribution of poikilotherms (Author et al. 2012).

Conclusion: We expect that climate change will impact the geographic ranges of poikilotherms.

Premise: Our results show that mangrove vegetation can trap mud.

Conclusion: We expect that mangrove removal will reduce mud trapping.

As you can see, premises are fairly straightforward. They are statements based on existing knowledge. In scientific papers, these can come from existing literature (e.g. Honeybees are a globally abundant species, Jones et al. 2015) or from the data you collected and analysed (e.g. We found a negative correlation between carbon engagement and the aggregate footprint). The conclusion is then drawn based on the premises.

The argumentation structure of a Discussion paragraph can be much more complex than a simple “one premise → one conclusion” structure. For example, conclusions can form the premise for the next argument, multiple premises can lead to multiple conclusions, etcetera. For the sake of simplicity, I’m showing simple arguments here. But if you’re curious, simply open up a paper and have a look at what’s really going on in the Discussion section.

How to form an argument?

To write a discussion, we need arguments. But how do we form those? If you look closely, you can see that arguments answer questions. For example, this argument answers the question ‘Will the sun rise tomorrow?’:

Question: Will the sun rise tomorrow?

Premise: Well, the sun rises every day

Conclusion: So I’d say that the sun will rise tomorrow as well.

In other words, we can use questions to form arguments. Here’s another example:

Question: Do certain types of scientists have shorter research careers than others?

Premise: In our study, we found that certain types of scientists have shorter research careers than others.

Conclusion: Thus, we argue that certain types of scientists have shorter research careers than others.

However, as you can see, this question leads to a boring and repetitive argument. To make it more interesting, we need to find a question with more context.

Using emotional context to pique interest

Context is the bigger, often societal, issue the research is trying to address. Generic examples are: “How can we address climate change”, “How can we save more (human or animal) lives”, “How does the universe work”, etcetera. They are the bigger questions that matter to humankind as a whole.

These big contextual questions often are often rooted in an emotion, such as curiosity (how does the world work), concern (climate change), or compassion (saving lives). We’re emotional beings, hence why we find these questions more ‘interesting’ than simply asking if something is true or falls.

However, such questions are also harder to answer, as they are usually too far removed from our data (i.e. premises) to provide a straightforward answer. Take for example this fictitious squirrel study:

Question: How can we preserve biodiversity?

Premise: New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts.

Conclusion: …?

It’s hard to jump to a conclusion here. We need to find a way to bridge the gap between this extremely general, abstract question, and the very specific finding about our squirrel populations.

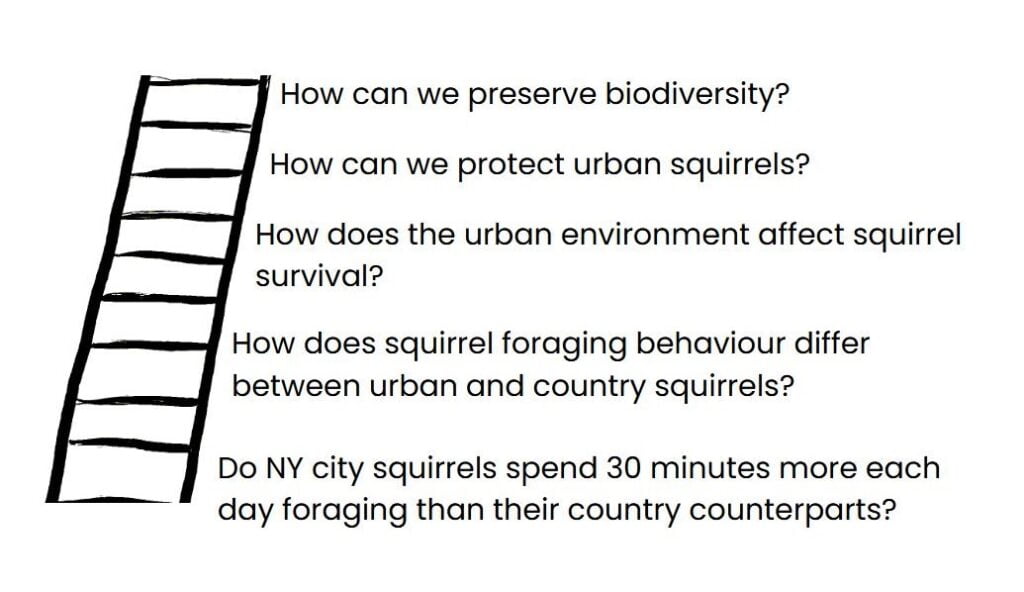

Bridging the gap with the Abstraction Ladder

To bridge that gap we need to find the levels of abstraction that exist between the specific finding and the general question. We can do this using the Abstraction Ladder.

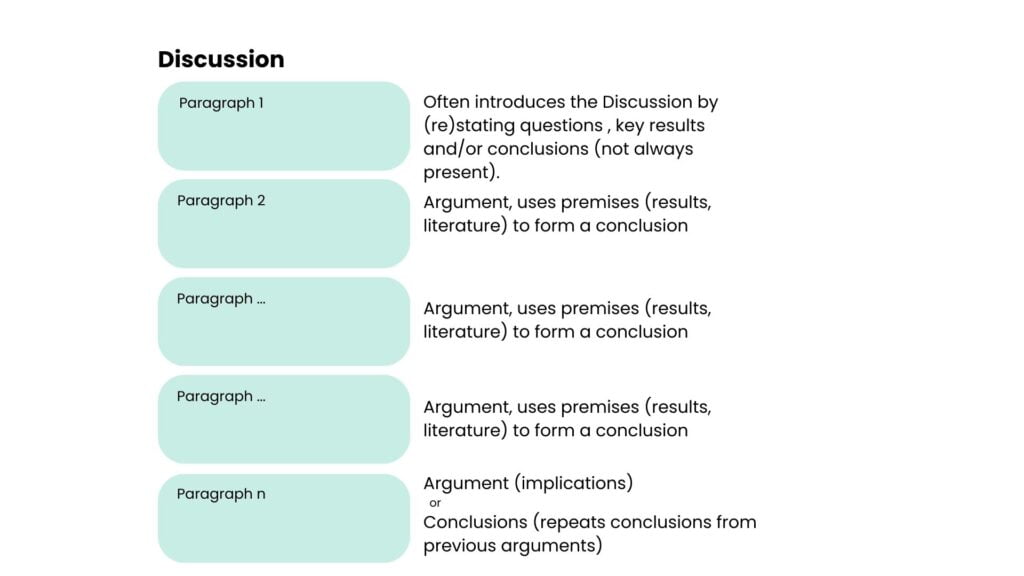

The Abstraction Ladder was introduced in the 1930’s by American linguist Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa and shows how you can move from specific concepts to abstract ideas. Here is his most famous example:

In this ladder, we move up from Bessie the cow all the way up to wealth. This ladder can be used in whatever direction we want. For example, with a bit of imagination we can also think of Bessie as a member of the community:

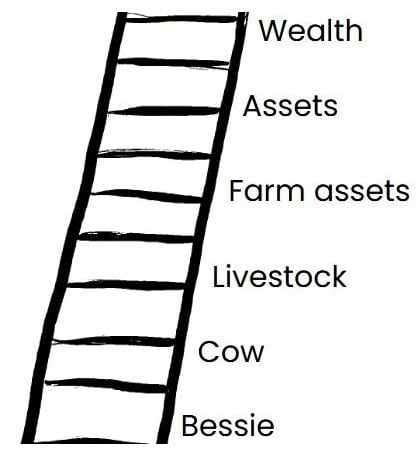

Now, let’s apply the ladder to our made-up squirrel study from earlier:

As you can see, I have edited the premise (NY city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts?) into a question by adding the word ‘Do‘, so that we have a question at both ends of the ladder (that’s just a bit easier to work with).

Now, we can start filling in the ladder with in-between questions. You can work from the top down or from the bottom up. Here, I’m going to work from the bottom up. First, I want to get rid of the closed-ended nature of this question:

Do New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts?

We can do this by, for example, adding the phrases such as ‘what’, ‘why’, or ‘how’. I’m going to use ‘how’:

How do New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts?

That’s a wonky question, so let’s rewrite it into something more sensible:

How much time do New York city squirrels spend foraging compared to their country counterparts?

That’s better, but now it’s a close-ended question again, so I’m going to have to fiddle around some more. Let’s do this by making ‘New York city squirrels’ a more abstract concept:

How much time do urban squirrels spend foraging compared to their country counterparts?

Let’s make the concept of ‘time spent foraging’ more abstract as well, by representing it with the more general concept ‘foraging behaviour’:

How does squirrel foraging behaviour differ between urban and country squirrels?

We can continue this exercise until we’ve reached the highly general question ‘How can we preserve biodiversity’:

Filling in the Abstraction Ladder can be a bit of a puzzle. It requires some creativity, looking at your results from different angles, and being okay with asking some really stupid and nonsensical questions (one of my initial question in writing this example was ‘Do squirrels like food?’, which, yes obviously they do, all animals like food 😅).

Now that we have a few questions, we need to pick one to write the argument. This will take some deliberation. If the question sits too low on the abstraction ladder, the argument will feel boring and repetitive:

Question: How does squirrel foraging behaviour differ between urban and country squirrels in our study?

Premise: New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts.

Conclusion: Urban squirrels spend more time each day foraging than country squirrels.

Paragraph: We found that New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts. Hence, we conclude that urban squirrels spend more time each day foraging than country squirrels.

Yet, as we saw before, if the question sits too high on the abstraction ladder, the argument is going to be impossible to make:

Question: How can we protect urban squirrels?

Premise: NY city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts.

Conclusion: …

There is not one way to find the right question. It’s based on understanding your audience, and what they find interesting. A good way to start is with trying out a few questions, and seeing which ones you find fun to answer. Because if you’re having fun with the question, chances are that others will find it interesting as well.

Writing up a simple argument

Once you have a question that think might work, you can start constructing the argument. After some playing around, I chose the question below:

Question: How does the urban environment affect squirrel survival?

Premise: New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts.

Conclusion: In terms of squirrel survival, we expect that squirrels are less likely to survive in the urban environment.

Paragraph: We found that New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than country squirrels. Hence, we expect that squirrels are less likely to survive in the urban environment.

This argument is better than the ones we made above, but it’s really flawed.

For one thing, it’s built on only one premise. Where is the supporting – and contradicting – literature?! What’s more, I’m implying that squirrel survival is directly related to time spent foraging, without even the slightest piece of evidence to back up that claim. Finally, I assume that foraging is the main driver of survival, but where’s the evidence for that? This is a major limitation to this made-up study that I need to address.

Here’s how I could rewrite the argument to make it better:

Question: How does the urban environment affect squirrel survival?

Premise: NY city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts.

Premise: Grimm et al. 2018 found that Berlin rodents spend up to and hour more time foraging.

Premise: Frick et al. 2005 showed that squirrels are less likely to survive when they need to spend more time foraging.

Conclusion: In terms of squirrel survival, we expect that squirrels are less likely to survive in the urban environment.

Paragraph: We found that New York city squirrels spend 30 minutes more each day foraging than their country counterparts. A previous study showed a similar effect, where urban rodents spent up to an hour more time foraging than country rodents (Grimm et al. 2018). Given the decreased survival rate that corresponds with increased foraging time (Frick et al. 2015), we expect that squirrels are less likely to survive in the urban environment. However, we recognise that we did not study how other aspects of city life might affect squirrel survival, and we recommend that future research look into such drivers, for example the impact of light pollution on urban squirrel survival.

This argument is still far from perfect, but it’s going somewhere. To improve it further, we could let loose our own inner critic, or perhaps get a supervisor or co-author involved to check what else we overlooked. But all in all, not too bad for a made-up study about urban squirrels.

Ultimately, writing the Discussion section is like solving a complex puzzle. Each result, every argument, and all the existing literature must fit together seamlessly to construct a compelling narrative. It takes time and a lot of mental effort, but it’s all the more satisfying when all the puzzle pieces finally click into place.

If you want to read more abstraction or making interesting arguments, I recommend reading this paper by Marcia Bundy Seabury entitled ‘Critical Thinking via the Abstraction Ladder’ or this one by Stephen R. Barley titled ‘Thoughts on What Makes a Paper Interesting’.