“Scientists need more time to think”. This message’s been plastered all over my LinkedIn feed for the past weeks. It comes from this Nature editorial, that talks about the impact of digital distractions on our ability to concentrate and produce good quality work:

“researchers […] need to slow down and spend more time thinking, to focus on maintaining and improving quality in their work,” says Cal Newport in the article.

You might know the guy. He’s a computer scientist and New York Times best selling author, known for his books Deep Work and Digital Minimalism. It seems that with his latest book, ‘Slow Productivity’, he’s struck a chord with the academic community. And with good reason.Because the quality of publications is indeed declining.

How to prioritise thinking?

To address this, the article discusses solutions such as visualising how ineffective it is to be constantly distracted, and limiting the length of our to-do-lists. It also delves into whether it’s feasible to add ‘thinking time’ as an item on our to-do-list (probably not), and suggests, in good scientific fashion, that we study in more detail how digital distractions impact the quality of science.

However, what the article doesn’t touch upon (maybe Newport’s book does, but in all honestly I haven’t read it), is why we struggle to prioritise thinking tasks. Yes, we get distracted. But why do we get distracted? Why do our brains prefer to write a quick email over working on a complex manuscript?

While I can’t answer that question for the entire academic population, I can answer it for myself. I prefer simpler tasks because they’re easier. I’m less likely to fail. So what to do? One obvious strategy is to break down complex tasks into smaller tasks. But does that work?

Make thinking tasks easier

Thinking tasks like designing an experiment, analysing data, reviewing literature, and writing journal articles are HUGE. They can stay on our to-do-lists for months, if not years. If we break down these big tasks into smaller tasks, it should be easier to move forward on them. Right?

Take writing a journal article. For the sake of example, we could break it down into these tasks:

* Write the Methods

* Write the Results

* Write the Discussion

* Write the Introduction

Each of these tasks is still quite big, so we’d have to break them down further. For example, we can break down ‘Write the Discussion’ as follows:

* Decide what to include in the Discussion

* Make an outline for the Discussion

* Write the Discussion

The tasks are smaller now, but they’re still hard! For example, how do you decide what to include in the Discussion? This is not a straightforward task; it still requires a lot of thinking. So making complex thinking tasks smaller doesn’t make them that much simpler. Instead, we may need to employ an extra strategy.

Redefine what ‘successful thinking’ means

Let’s have a look again at why I prefer simpler tasks – they’re easier. And I like easier tasks because I’m less likely to fail. So that means I feel like I’m failing when I’m doing hard tasks – hence why I prefer to avoid them.

Allow me to illustrate:

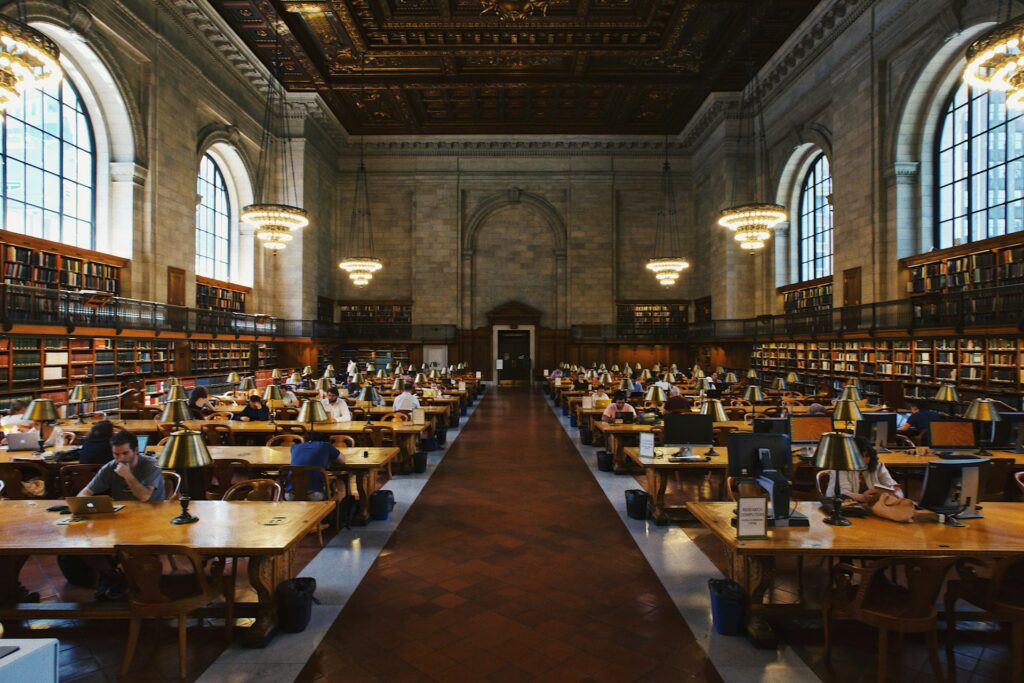

When I heard the words ‘deep thinking’ or ‘thinking time’ as PhD student, I pictured myself sitting in an old academic library writing one insightful thought after the other in my notebook. I was creating, in a flow, coming up with amazing new insights.

Photo by Robert Bye via Unsplash

So, with this ideal in mind, I would sometimes tell myself: today I’m going to get a lot of writing done!

But all I could produce were a few meager sentences, because just when I thought I had a grasp on things, I discovered a new fact that completely messed up my current understanding of the problem at hand.

Missing information.

Unknown variables.

Endless what-ifs.

At the of the day, I would feel deflated, because I had failed to think productively. But was that really true? No, of course not.

What I failed to realise, was that all that mucking about and running into dead ends was, in fact, incredibly productive. I had spent the entire day thinking!

I had spent time thinking through all the ways in which my results didn’t make sense. I had found all the ways in which I could not interpret my findings.

I found all the solutions that didn’t work.

By failing to think up interesting interpretations, I laid the groundwork for finding all the ways in which my research did make sense. All that ‘failed’ thinking was incredibly productive.

3 strategies to feel positive about challenging thinking tasks

So to prioritise thinking time, we need to feel good about working on complex thinking tasks. Here are a few strategies I use to achieve that:

- Define the problem you want to solve before you start thinking. For example ‘figure out who to cite’, ‘decide on the correct statistical analysis for my data’, ‘decide on a colour scheme for the figures’, ‘figure out whether my results mean something good or something bad for the world’, etc. Note that ‘defining the problem’ can be a problem in itself!

- Reflect on your thinking session (designing experiments, compiling data, assessing results, reviewing literature, writing, etc.). What new questions did you uncover? What do you know now that you didn’t know before? Do you feel like you have a better grasp on the problem at hand now?

- Time your thinking session. Instead of measuring and valuing thinking time by outcomes, measure it by time spent thinking (don’t forget to include those times you weren’t actively working, but still churning on the problem, like when you were going for a walk).

What do you think? Will these strategies help to prioritise thinking time? Or do we need different solutions to maintain the good quality of scientific work?